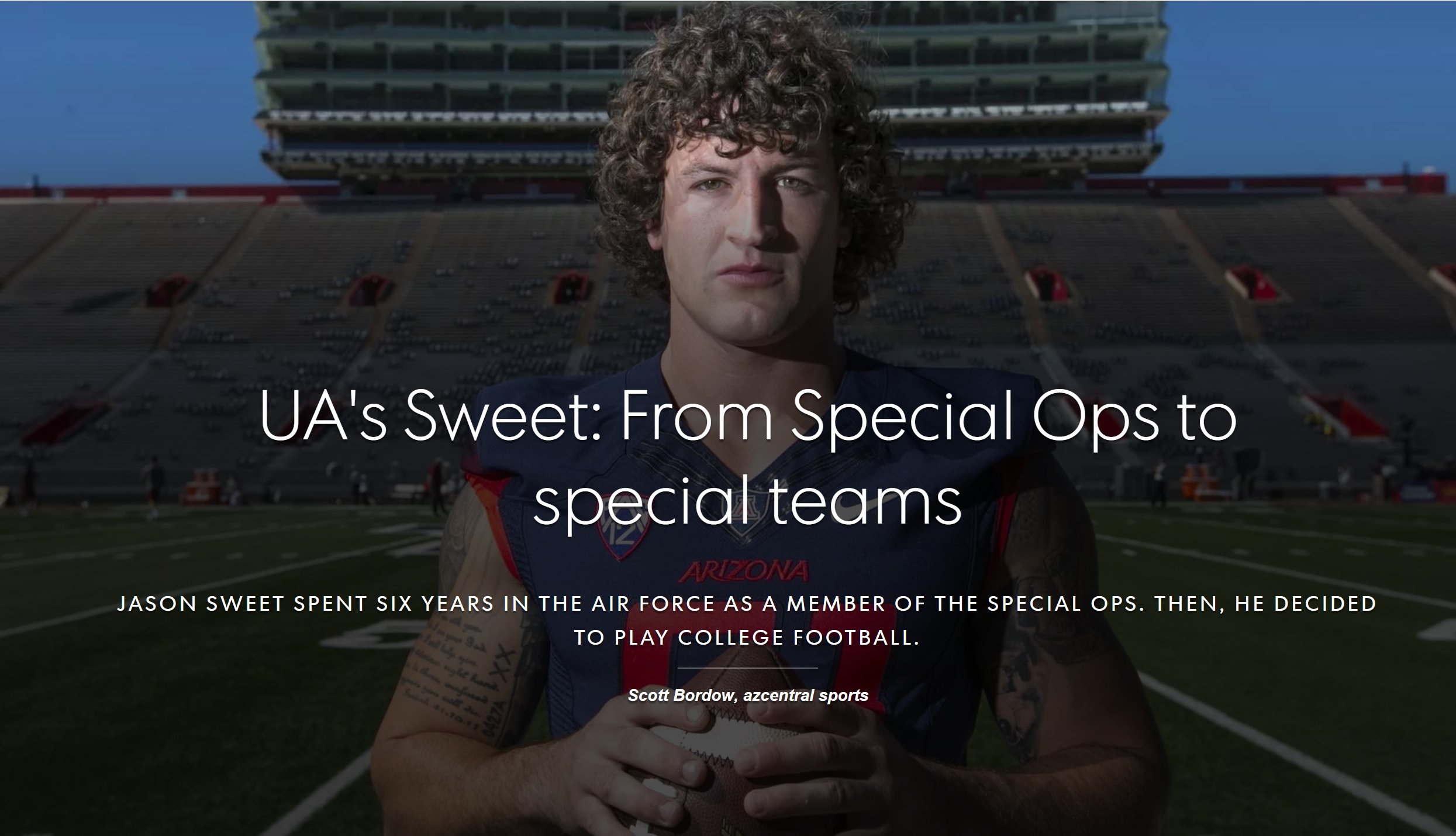

U.S. AIR FORCE VETERAN – JASON SWEET

About This Project

Jason Sweet sits down, his 6-foot-2, 222-pound frame all but suffocating the chair. His tattooed arms strain the University of Arizona red Nike tank top he’s wearing. A long, vertical scar runs down his right knee.It’s a Monday afternoon and the rain is pounding the streets outside the Lowell-Stevens Football Facility on the UA campus. Sweet places his backpack beside the chair. He has class in an hour.

The tape recorder is turned on. For 51 minutes, Sweet tells his story, his words spilling out softly but at a rapid pace. When he’s through, the UA public-relations official who had set up the interview is still standing nearby.

“I was going to leave,” he says, “but then I started listening to him. Pretty amazing, isn’t it?”

Yes, it is.

***

How do you begin to tell a story about a young man who had to give up his dream of playing professional baseball when his pitching arm gave out, survived two brutal years of training to become an Air Force Special Operations pararescue jumper, served in Afghanistan for three months, and, then, at the age of 26, made the Arizona football team as a linebacker/special teams player after failing his first tryout months earlier?

Perhaps like this: He won’t take no for an answer.

“His life is anything but a conventional path,” said Sweet’s father, Maurice Sweet. “I think it shows how unique and special he is.”

“I want to be a doctor but, damn, I love football. That’s who I am. I’m a football player.”

Jason Sweet

That path began at Payson High School, where Sweet played baseball and football before graduating in 2007. He received a scholarship offer to play baseball at Grand Canyon University, but in his freshman year, his pitching arm gave out. Once able to throw a 91-mph fastball, he could barely top 80. His dream of playing professional baseball was over.

“My gift was gone,” Sweet said. “I was lost.”

Sweet prayed about what he should do next. He recalled the stories his dad told about his days as a pararescue jumper, tales of skydiving and scuba diving, shooting and mountaineering. Sweet had wanted to become a Navy Seal since he was little, but as he explored the two jobs, his choice became clear.

According to military.com, pararescue jumpers – or PJs as they call themselves – are “the only Department of Defense specialty specifically trained and equipped to conduct conventional or unconventional rescue operations.” The pararescue motto – “That Others May Live” – appealed to Sweet.

“Seals go on a mission to take a life. PJs go on a mission to save somebody who’s isolated and having the worst day of his life,” Sweet said. “If you combine someone who has the utmost aggression and the utmost compassion, that’s me.”

Sweet passed his interview and tryout for the 306th Rescue Squadron at Davis-Monthan Air Force base in Tucson and then began the two-year training program recruits have to pass to earn the pararescue jumper’s maroon beret. The training, known as the “The Pipeline,” or “Superman School,” begins with a 10-week indoctrination course at Lackland (Texas) Air Force Base. It’s there that the physical, mental and emotional rigors of training break most men.

“If you combine someone who has the utmost aggression and the utmost compassion, that’s me,” Jason Sweet said.

(Photo: David Wallace/azcentral sports)

The on-land physical demands — a six-mile run every day, instructors telling recruits to drop and give them 50 push-ups — were tough enough. But, according to Maurice Sweet, it’s the in-water exercises that break most recruits.

“They take away your ability to breathe for a long time,” Maurice Sweet said. “I had former Nebraska football players in my squadron who didn’t make it because they couldn’t get comfortable with not being able to breathe.”

In one exercise called “water confidence,” recruits have to tie knots underwater while instructors are splashing them and moving their masks around. In another, two recruits have to share a snorkel to breathe while instructors are splashing them and pushing their bodies apart.

“They’re putting your body under a lot of stress,” Maurice Sweet said. “I think the physical demands are just simply not what a typical person wants to endure.”

Sweet said his unit began with 100 recruits; by the third week only 28 were left.The two-year program has an 85 percent attrition rate.

“You think of quitting every day when you see grown men next to you crying and you realize that this is only the second week,” Sweet said. “But it’s necessary. If you’re having the worst day of your life and you’re behind enemy lines, you want somebody who is not going to break, who is going to come to get you at all costs.”

Sweet had it worse than most. Some of the trainers at Lackland knew Maurice Sweet had been a pararescue jumper and had trained his son in order to make him as prepared as possible for indoc training. They called Maurice and asked, “How good is your boy? We’re fixing to take him to a different level.”

“There was no option to quit. None.”

Jason Sweet

“I told one instructor, ‘He’s a bad dude,’ ” Maurice Sweet recalled. “He told Jason, ‘I talked to your dad, and he said he can do whatever I want to you. Sweet, prepare to die.’ ”

Sweet wouldn’t break. His baseball career was over. He had nowhere else to go. And he wouldn’t go home to his father “dishonored.”

“There was no option to quit. None,” Sweet said.

He got through indoc school and the rest of “The Pipeline,” including the 22-week course to earn an EMT-Paramedic certification and the 24-week Pararescue Recovery Specialist Course, which trains recruits in field tactics, mountaineering, combat tactics, advanced parachuting and helicopter insertion/extraction.

After receiving his beret, Sweet returned to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base as a pararescue jumper reservist. But he wanted to fight for his country. So, in March 2012, after additional training, he was on a flight to Afghanistan.

Former Payson football and baseball standout Jason Sweet is now a linebacker at Arizona. But he took a detour as a paratrooper before landing on Rich Rodriguez’s squad.

Sweet doesn’t talk much about his time in Afghanistan other than to provide the basics: He said he served in the Helmut Province of Afghanistan and flew 72 missions.

He doesn’t want to be seen as special or doing anything extraordinary compared to his fellow troopers.

“I’ve been in some big-time situations, but if there’s anything my leadership would have wanted to take away from my job it would be to be humble,” Sweet said. “I have guys on my team that have been on missions that are just so much more heroic than the missions I have been on. They’ve done amazing things, and you won’t ever know about it. So, I cannot take credit for anything I’ve done over there when there are heroes like that walking around. They deserve the credit, not me.”

“He’s a young man kids want to be around. They want to spend time with him outside football. They look at him kind of like a big brother.”

UA special teams coach Charlie Ragle

Sweet will talk about one mission because it laid the groundwork for what he plans to do the rest of his life. His team was told it needed to pick up a 9-year-old Afghan boy whose father was “of high importance.” The boy had been shot in the torso three times by the Taliban. Sweet’s team rescued the boy while under Taliban fire and dropped him off at an Afghan hospital. When they returned to the base, they were told to go out and get the boy again, that he was dying.

“I thought about him all night,” Sweet said. “We went on another mission to the hospital the next morning and I asked the doctor how he was doing. He said, ‘We had to take out his spleen and do a whole lot of plastic surgery but he’s alive.’

“That was the best feeling I’ve ever had. I want to feel that all the time. It’s what started me wanting to become a doctor.”

First, however, there was an itch he still had to scratch.

***

Sweet enrolled at Pima Community College in 2013 with the hope of playing baseball again. But his arm didn’t have any life left in it. One morning that summer, as he sat in his kitchen, he thought, “Why don’t you play some football for the UA?”

He was 25 years old. He had played one year of high school football at Payson. The idea was ridiculous.

But Sweet wouldn’t take no for an answer. He hired a speed coach and started working out at a mixed martial arts gym. He became a student at UA in January 2014 and, in March, he tried out for the team.

He was cut. He had trained so hard that his legs were dead the day of the tryout and he ran a 5.05 40-yard dash.

That should have been the end. He was too old and too slow. In August 2014, Sweet left for Cocoa Beach, Fla., to take the pararescue jumpmaster course. But as he trained, he kept thinking about football and about failing.

“I started telling myself, ‘Why would you quit now? You’ve never quit. You’re not a quitter,’ ” Sweet said.

He returned to Tucson after completing the jumpmaster course and again began training. In September 2014, he had a second tryout. This time, he ran a 4.67 40-yard dash and made the team.

Several weeks later, he played special teams against USC.

“He’s just an amazing person who has done a lot of things right with his life,” Maurice Sweet (not pictured) said of his son Jason.

(Photo: David Wallace/azcentral sports)

“I think it says a lot about him, that dogged personality,” Maurice Sweet said. “He just doesn’t give up at anything.”

UA special teams coach Charlie Ragle said Sweet might have played a bigger role on special teams this year had he not torn the anterior cruciate ligament in his right knee while training in June. Still, Ragle said, Sweet’s teammates have gravitated to him.

“He’s a young man kids want to be around,” Ragle said. “They want to spend time with him outside football. They look at him kind of like a big brother. He gives them guidance and wisdom, but he’s also young enough to relate to them. That speaks to his leadership characteristics.”

Sweet, 27, left the Air Force in October 2014. He’s a full-time student, majoring in molecular and cellular biology, the memory of that 9-year-old boy pushing him to become a trauma surgeon.

“I want to be a doctor but, damn, I love football,” Sweet said. “That’s who I am. I’m a football player.”

He’s more than that. He’s an athlete and a scholar, a future doctor and a pararescue jumper. His dance card, it seems, will always be full.

“He’s so unique and so gifted in so many things,” Maurice Sweet said. “He’s just an amazing person who has done a lot of things right with his life.”

Story provided by Scott Bordow

Reach Bordow at scott.bordow@arizonarepublic.com or 602-448-8716. Follow him at Twitter.com/sBordow.